It took an emotionally complex man to first imagine a world in which machines could ‘think’, writes Satyen K. Bordoloi

I don’t recall the AI system I was tinkering with back in 2019, but I remember my reaction: a surprised chuckle. This was before LLMs became as common as phones. I had asked this nascent intelligence to create an original joke. Curious, yet convinced the system must have scooped it up from the internet, I conducted a thorough search on various search engines.

I found similar structures and setups, but never the exact joke. It left me convinced the AI had managed to synthesise and recombine what existed to create something entirely new, eliciting a spontaneous, human response from me. I recall thinking at the time: Have machines already passed the Turing Test?

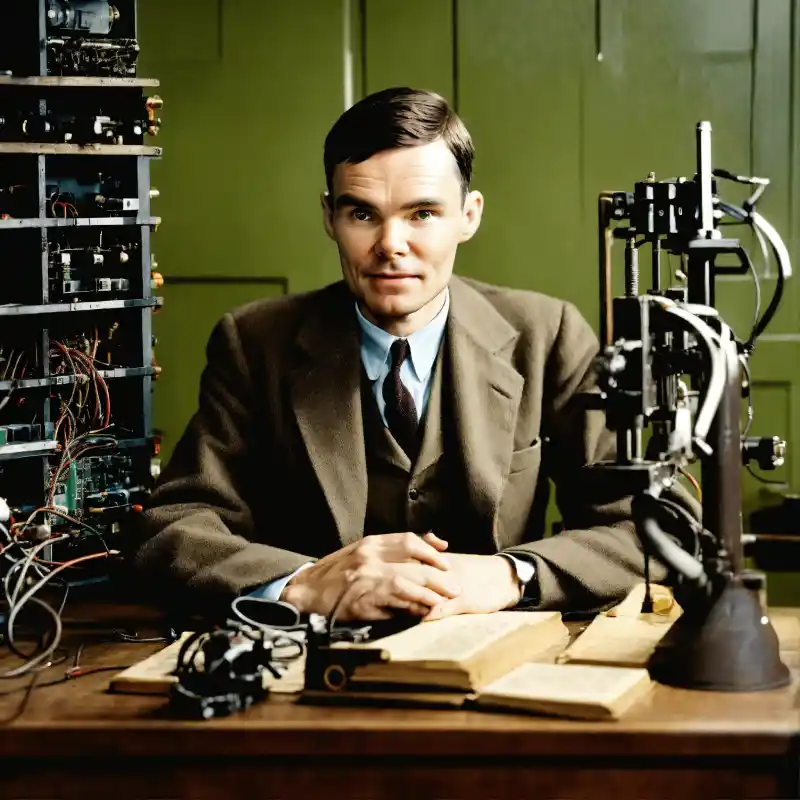

The man who formulated that test was Alan Turing. He wasn’t an emotional man from a sentimental perspective; instead, he was a logician, a cryptanalyst, a man who thought in codes and algorithms – think Neo from The Matrix, who could see the code around him. To him, as evident from his writings, emotions were not a frivolous affect, but fundamental to human cognition and communication; that our humanity is often expressed through response-dependent concepts, seemingly irrational yet meaningful arguments, and interactions based on feelings.

In 1950, he turned these insights into a paper that would change the world for a second time; the first was via his seminal 1936 paper on the Turing Machine – a theoretical idea of a computer which paved the way for every computing device since, and our digital age.

The 1950 paper published in the journal Mind was titled Computing Machinery and Intelligence and began with a deceptively simple question: “Can machines think?” It smartly evaded the philosophical minefield of defining “thought” and instead proposed a practical alternative: a game. In his Imitation Game (on which the Oscar-winning movie is named, a crucial and metaphorical departure from the book that took its name from the World War II machine Turing decoded), a human interrogator chats with two unseen respondents, a human and a machine.

If they cannot tell the machine from the human, then that machine, for all practical purposes, has demonstrated behaviour we can call ‘intelligent’. This was the Turing Test: the first and most influential benchmark for understanding machine intelligence.

The Turing Test helped us distinguish between the wheat and the chaff; for example, it made it easy to call out early chatbots like ELIZA as little more than parlour tricks, while also laying the path to true AI. I believe we crossed the threshold on February 16, 2011, not in a lab but on a game show when IBM’s Watson won at Jeopardy! Watson, on that show, wasn’t just parsing data; it understood nuance, context, and wordplay of the English language.

That victory heralded the new era of Artificial Intelligence we are living in right now. Since then, progress in the field has been exponential, marked by a compounding of speed, scale, and sophistication in everything that falls under the umbrella we call AI.

However, the breakthrough came in a deceptively simple Google paper, titled Attention Is All You Need, in 2017, where the concept of Transformers was proposed. This paper formulated the ideas that gave birth to what we now know as Large Language Models (the ‘T’ in ChatGPT stands for Transformer), and AI as a field went beyond what even Turing perhaps ever imagined.

The proof of the pudding is in the eating, goes the cliché and this proof came via an unlikely execution of the Turing Test. In 2022, Google engineer Blake Lemoine, after chatting with their LLM LaMDA, began to believe that the system was not only self-aware but also had emotional depth and showed a desire to have rights.

Lemoine, unwittingly, became a participant in a real-life Turing Test, where the human in question was not only fooled into believing the machine was human, but he was also profoundly moved. The illusion of sentience becoming as powerful as real sentience: that’s the Turing test fulfilled.

The result is that today we live in a world that would have surprised Turing himself. People are having affairs and relationships with chatbots, AI clones of actual people and AI avatars. We have turned Turing’s conception upside down with customer service bots expressing digital empathy while we humans, frazzled and struggling for time, respond with curt, machine-like efficiency to our friends and family.

Our social media feeds curated under the watchful ‘eyes’ of powerful algorithms amplify the worst of us by trapping us in dangerous digital echo chambers. We have come to a point where the responses of machines are often more measured and “human” than our own, as our own discourse adopts the brutal, binary logic of a machine: right or wrong, Left or Right, my way or the highway. The question to me, thus, is no longer whether a machine can pass for human, but whether we are failing to.

This brings us to the tragic fate that looms over Turing’s legacy. The man who conceptualised machines to be as good as us was broken by the worst of what is in humans. Being gay and honest in post-war Britain proved deadly, as after admitting to a relationship with another man, the saviour of countless Allied lives during World War II was offered a choice: imprisonment or chemical castration.

Choosing the latter, thus being injected with synthetic estrogen to cure him, devastated him physically and psychologically. The father of computer science and thus our digital age, and the grandfather of AI, a man whose work would go on to save millions and billions as time goes on, and enrich trillions of lives if we don’t destroy ourselves, was hounded to his death by the very society he saved.

At 41, Alan Turing was found dead from cyanide poisoning with a verdict of suicide. If Socrates was the first martyr of Democracy, Turing wasn’t even the last to lay down his life at the altar of human prejudice.

The supreme irony of our age is that the same regressive morality that killed Turing is getting a new lease of life, indeed growing exponentially, thanks to greedy social media companies, who, in the pursuit of engagement and profit, are using the very AI Turing helped birth to accentuate bias, bigotry and discrimination. From fundamentalist interpretations of Islam and Judaism on the rise to the homophobic ideas of some Christian nationalist movements, the world is fighting back against a diverse, inclusive, and tolerant world.

In 64 nations, being gay is a crime, and in 12, it’s punishable by death, a brutality increasingly justified by many, tutored as they are by the extreme ideas that pop onto their feeds by algorithms. Regressive ideas of every religion are being spread like wildfire by AI, destroying over 2500-year-old forests of tolerance and inclusion painstakingly built to protect those like Turing.

This is the paradox we are living in. We are in awe of machines that can mimic human conversation, yet stay blind to the creeping mechanisation, the machine-induced violence of our own souls. We fearmonger over the rise of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) while willingly outsourcing our empathy, thinking, and morality to algorithms.

We have turned the Turing Test for machines into a historical curiosity simply because the urgent, pressing question for our time isn’t about the humanity of machines, but the lack of it in humans.

We need a new Turing Test, but this time for ourselves: to judge not intelligence but wisdom, not correctness but empathy, not the ability to imitate but the capacity for compassion.

Can we, when faced with those different from us in colour, caste, creed or orientation, respond with curiosity instead of contempt? Can our political, cultural and everyday discourses pass a test of basic human decency? Can we reflect on the fate of Alan Turing and feel not just historical sadness, but a fierce, current determination never to let such brutality rule over us again?

As we mark 75 years of the Turing Test, we stand at a crossroad: the road of silicon criss-crosses the one made of spirit. The machines watch us, and learn from the data of our lives, and, sadly, from our greatest art and our worst prejudices. They become our mirrors, and what they are beginning to reflect back at us is a startling image.

The 75 years of the Turing test tell us that true intelligence is not the replication of logic, but the preservation of love, the courage of kindness, and the defiant, beautiful, and often irrational capacity to care for each other. This is the real test that we must strive to pass. That’s because if you look at Turing’s life along with his work, you realise his legacy is not just whether machines can think, but it is a plea for humans to feel, to be accepting, and to love more deeply than any algorithm ever could.

In case you missed:

- Why the Alleged, Upcoming AI Crash Is Never Going To Happen

- One Year of No-camera Filmmaking: How AI Rewrote Rules of Cinema Forever

- Greatest irony of the AI age: Humans being increasingly hired to clean AI slop

- To Be or Not to Be Polite With AI? Answer: It’s Complicated (& Hilarious)

- AI Hallucinations Are a Lie; Here’s What Really Happens Inside ChatGPT

- AI Washing: Because Even Your Toothbrush Needs to Be “Smart” Now

- Don’t Mind Your Language with AI: LLMs work best when mistreated?

- AI Adoption is useless if person using it is dumb; productivity doubles for smart humans

- Anthropomorphisation of AI: Why Can’t We Stop Believing AI Will End the World?

- The Digital Yes-Man: When AI Enabler Becomes Your Enemy