Decades before ChatGPT, two economists modelled ‘creative destruction’ while a third found out why societies fail. In 2025, their Nobel prize becomes a survival guide for the next two centuries and beyond, finds Satyen K. Bordoloi.

The theme song of The Big Bang Theory goes:

Our whole universe was in a hot dense state,

Then nearly fourteen billion years ago expansion started

From all those 14 billion years, till about 200 years ago, human progress was like the clichéd old scooter in Hindi cinema – it sputtered, rather than roar to life.

However, just as the rest of the song goes –

Math, science, history, unravelling the mystery,

That all started with the big bang!,

Just over two centuries ago, along with the Industrial Revolution, humans also had a big bang of economic growth and, contrary to all logic, it hasn’t yet stopped growing, again – just like the big bang.

Three economists spent their life trying to understand how this happened. And this year, the work of this trio – Joel Mokyr, along with Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt – has been rewarded with the prestigious Nobel Prize in economics “for having explained innovation-driven economic growth”. This comes at just the right time, as Artificial Intelligence today and quantum technologies tomorrow are set to do exactly what this trio has found happened in the economic history of humankind. But first, let’s try to understand their work from the ground up.

THE GREAT STAGNATION

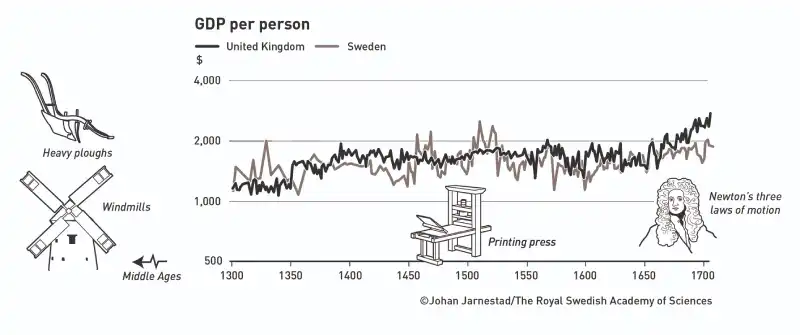

Pyramids, ancient Athens, Rome & Baghdad, Ajanta & Ellora, etc., are proof that we have had spurts of brilliance. Despite the occasional flashes, the living standards of the world remained largely unchanged from one generation to the next. The world was stuck in a sort of ‘great stagnation’ – technological advances would sputter only to fizzle out, leaving our ancestors with nothing more than stories of what was. And remember this is even as the brains of our ancestors are not any different from yours and mine.

Take the windmill and printing press – both brilliant innovations that failed to spark sustained progress. After temporary bursts of improvement, societies returned to the economic status quo. This was because innovation occurred in isolation – without the necessary ecosystem to build upon previous advances.

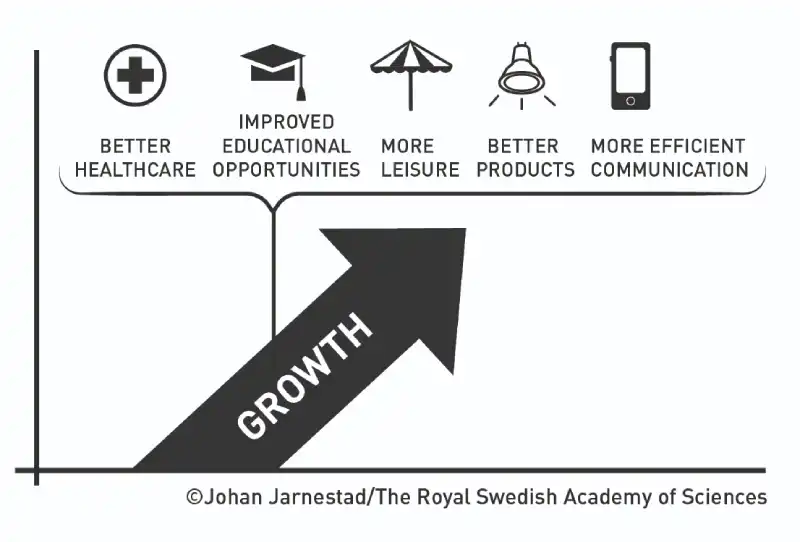

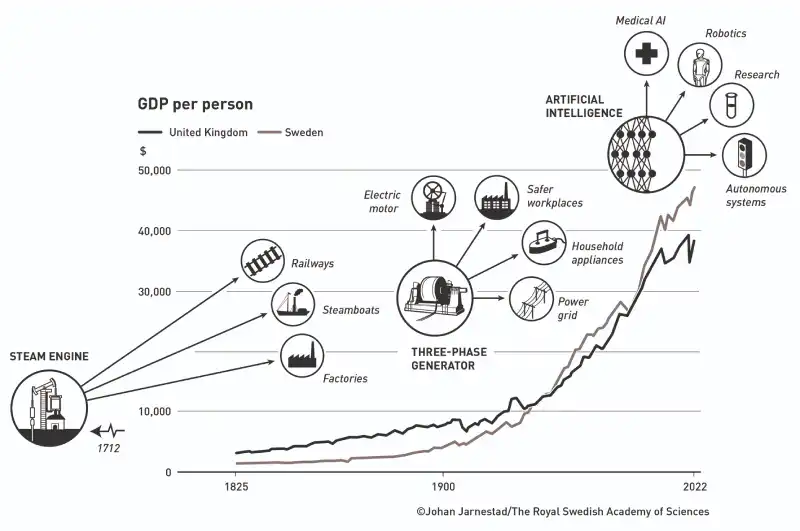

However, about 200 years ago, everything changed. The Industrial Revolution kick-started in the UK, and unlike the previous 11,000 years of our modern civilisation, this one stuck. Growth – not stagnation – stayed the new normal with every industrialised nation experiencing sustained annual growth of almost two per cent, modest by the look of it, but its compounding effect doubled income over a human’s life and fundamentally transformed everything. It was truly revolutionary.

What changed? Like The Big Bang Theory title track, this year’s Economics Nobel laureates have spent their lives with “Math, science, history, (for) unravelling the mystery.” And what they found landed at just the right time.

JOEL MOKYR’S KNOWLEDGE REVOLUTION

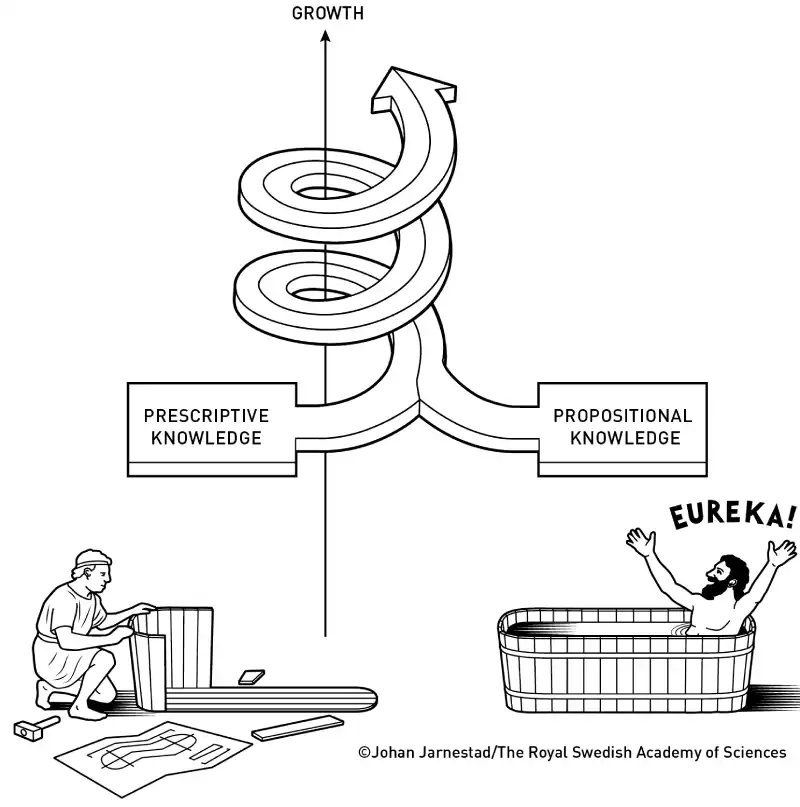

Joel Mokyr, an economic historian at Northwestern University, discovered that the critical difference between earlier flashes of innovation and the sustained growth of the last 200 years came down to what he calls “useful knowledge“. He identified two essential types of knowledge: “propositional knowledge” (understanding why something works) and “prescriptive knowledge” (knowing how to make it work).

Before the Industrial Revolution, both existed in separate silos. Craftsmen knew how to make things work through trial and error, while scientists understood natural principles without practical application. It was like having recipe writers who had never picked up a spatula, and chefs who didn’t understand ingredients.

The ancient Greeks, Romans, Indians, and Chinese, and especially the Muslims of the Middle East 1000 years ago, each possessed both types of knowledge. Still, they never bound them until the Scientific Revolution and Enlightenment lit up Italy and gradually spread to the world by introducing precise measurement, controlled experiments, and reproducible results. This led to a feedback loop between theory and practice. Suddenly, understanding atmospheric pressure helped improve steam engines, and insights into metallurgy could increase steel production. Knowledge began to compound, build upon itself in a self-reinforcing cycle. However, it wasn’t enough.

Mokyr identified another crucial ingredient: societal openness to change. Britain became the cradle of sustained growth not only because of its knowledge ecosystem but also due to its skilled artisans who could transform ideas into commercial products, and institutions like the British Parliament that prevented established interests from blocking progress. When resistance to innovation emerged – as it always does – Britain had mechanisms ready to prevent the sore losers from sabotaging the emerging winners’ gains, no matter how powerful the losers were.

Aghion and Howitt’s Dance of Creative Destruction: While Mokyr spent time digging through historical archives, economists Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt were probing the same ideas by constructing a mathematical framework that captured the turbulent dynamics of modern growth. Their ground breaking 1992 model gave form to the process where new products and companies displace old ones in a never-ending cycle of economic renewal, which economist Joseph Schumpeter called “creative destruction.”

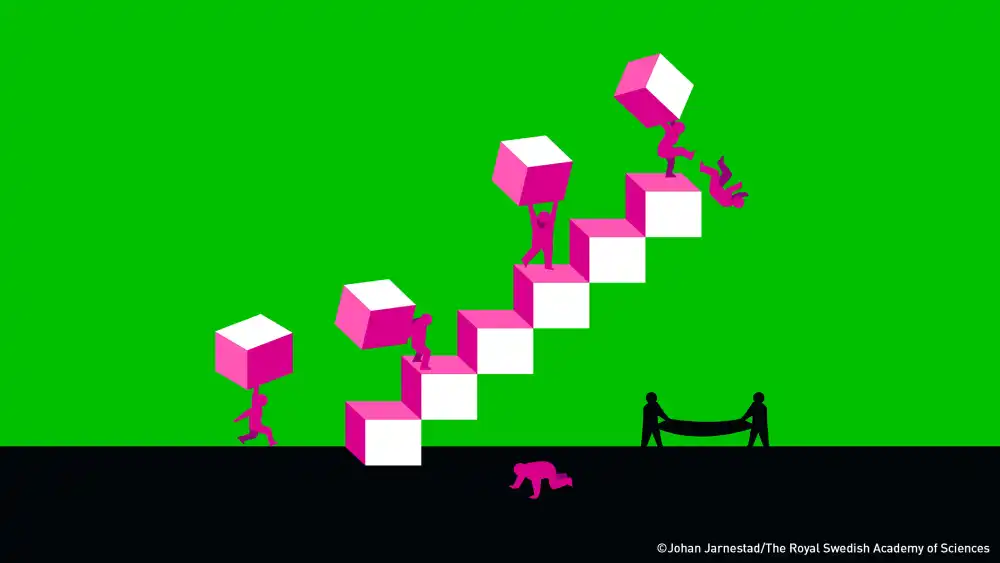

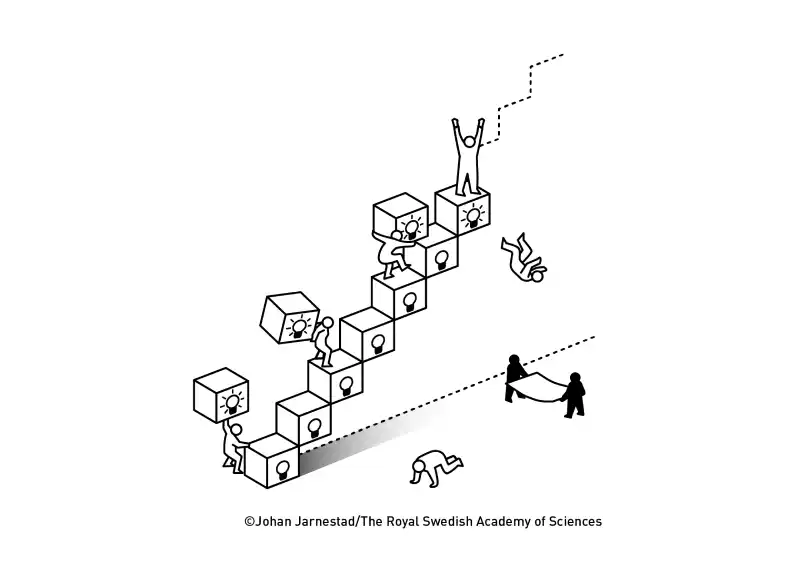

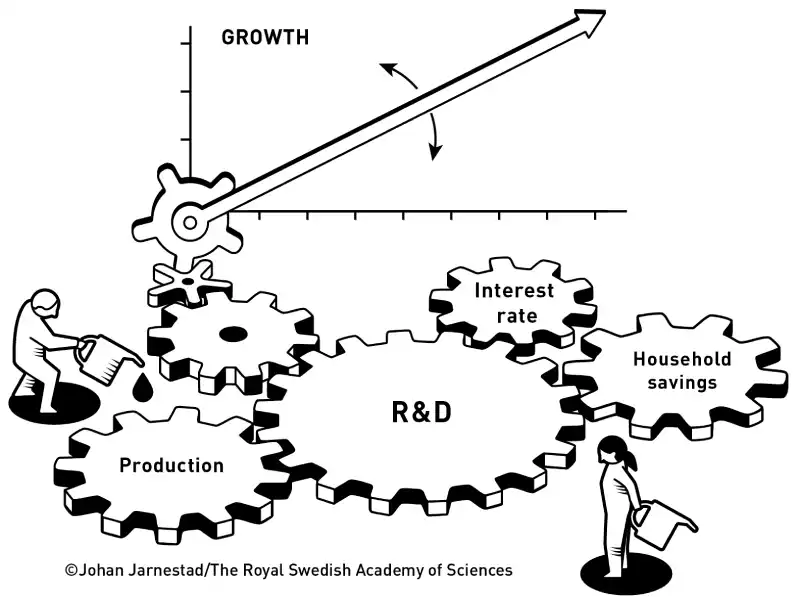

Imagine the economy as a crowded ladder, with each rung representing a company and its technology. A company climbs to the top through innovation and builds a temporary monopoly thanks to patents, which Aghion and Howitt call being “at the top of the ladder”. However, this privileged position is constantly threatened by other companies developing even better innovations in the same category. The potential for such monopolies creates the incentives needed for investments in research and development (R&D), which in turn determines the speed of creative destruction and economic growth.

Their model became the first macroeconomic framework for creative destruction, integrating production, R&D, financial markets, and household savings into a cohesive whole. Previous models couldn’t answer whether market-driven R&D was optimal for society. Aghion and Howitt discovered two competing forces: that innovations benefit society more than the innovator (suggesting we need more R&D), while also suggesting that “business stealing” effects can make private returns exceed social benefits (suggesting too much R&D). The balance between these forces varies across markets and time, providing policymakers with nuanced guidance on where to provide R&D support.

Is AI’s Economic Turbulence a Good Thing: This brings us to a kind of creative destruction happening around us right now, caused by none other than AI. The same dynamics Aghion and Howitt identified are happening around us with AI companies and what they’re creating, and the disruption of everything from creative work to professional services. It is not that AI can churn out a song as good as any A R Rehman has created in just 20 seconds, but what it is doing to those out there reliant on the creativity of their minds for earning their living.

On the other hand, it is a simple fact that in the US alone, about 10% of all companies go bust every year, and just as many are born. This isn’t a sign of economic sickness, but the opposite; it signifies economic health, much like the 60 billion cells dying every day in your cells is a sign of health. This birth and rebirth inside the economy is what Aghion and Howitt described.

The current AI revolution exemplifies this perfectly: established companies are racing to incorporate AI, while startups are emerging with potentially disruptive approaches. Pitted against each other are doomsayers who fear existential risk from AI and accelerationists who want rapid deployment, reenacting ancient debates about technological change. The challenge, as the Nobel prize-winning economists rightly have written about, is managing the transition wisely. The concentration of AI power in a few companies is a threat to the cycle of creative destruction. If the AI innovation resources like data, computing power and talent get locked inside monopolistic silos, we risk replacing dynamic competition with entrenched power.

Thus, the 2025 Economic Nobel to these couldn’t have been better timed, coming as it does after 200 years of sustained growth, but also threats to that growth from new technologies. The work of these economic scientists tells us that growth isn’t automatic, but emerges from cultivating the delicate ecosystem of knowledge, competition and openness, which together make innovation a reality. Their work tells us that progress demands neither unchecked tech acceleration nor resistance to change, but rather wisdom to nurture creative destruction while managing its consequences.

Amid the storm of AI and the impending one of quantum computing, it is important to keep the work of these economists as a guiding light. If we do, then perhaps we can guarantee another 200 years of ceaseless growth. Fail, and we might not just experience stagnation, but even regression to the ways of 200 years ago. The choice, as they always say, is ours in the present.

As dogmatism rises, science recedes. The 2025 Economics Nobel is thus not just honouring three brilliant minds, it is giving us the blueprint to fight back to secure our futures. And for their: “Math, science, history, unravelling the mystery,” the Nobel committee itself deserves to be nominated, for a Nobel.

In case you missed:

- AI Adoption is useless if person using it is dumb; productivity doubles for smart humans

- Why Elon Musk is Jealous of India’s UPI (And Why It’s Terrifyingly Fragile)

- How India Can Effectively Fight Trump’s Tariffs With AI

- DeepSeek not the only Chinese model to upset AI-pple cart; here’s dozen more

- Deep Impact: How Cheap AI like DeepSeek Could Upend Capitalism

- 95% Companies Failing with AI? An MIT NANDA Report Misread by All

- Quantum Leaps in Science: AI as the Assembly Line of Discovery

- When AI Meets Metal: How the Marriage of AI & Robotics Will Change the World

- Disney’s $1B OpenAI Bet: Did Hollywood Just Surrender to AI?

- From Generics to Genius: The AI Revolution Reshaping Indian Pharma