The 2-billion-year-old genome of life on Earth could be contaminated beyond redemption writes Satyen K. Bordoloi

Radioactivity-measuring Geiger counters have a unique requirement. Its iron must come from steel produced before 1945. Nuclear tests have contaminated all of the planet’s air so much that the steel produced since is not sensitive enough to detect radiation accurately. Where do humans find this ‘low-background steel’ for Geiger counters? Ships that sank before 1945.

The 2020s – much like 1945 – will be a cut-off decade for the purity of the human genome. As we go deeper into the future, we will not be able to guarantee that our genome – crafted at the smelter of nature for 2 billion years – will remain untrammelled. The reason is gene editing.

Gene alterations promise two things: magical cures for incurable diseases and later, enhanced humans. This Wired article rightly proclaims, ‘The Era of One-Shot, Multimillion-Dollar Genetic Cures Is Here‘. But it also comes with an infinite potential for disaster.

What is a gene and how is it edited

Genes are distinct sequences of nucleotides in chromosomes, most of which act as instructions to make molecules to form different types of proteins. A human body may have anything from a few hundred DNA bases to over 2 million. The Human Genome Project identified nearly 25,000 human genes. These genes are the basic unit of heredity and are passed from parent to child.

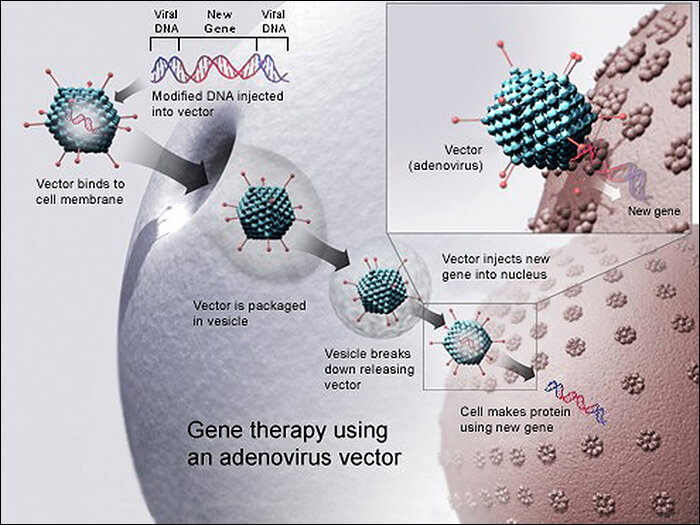

Thus technically, if you could change a gene, you could change the instruction given to a molecule. The part of the body that is targeted in gene editing, will work based on the new information in the new gene inserted.

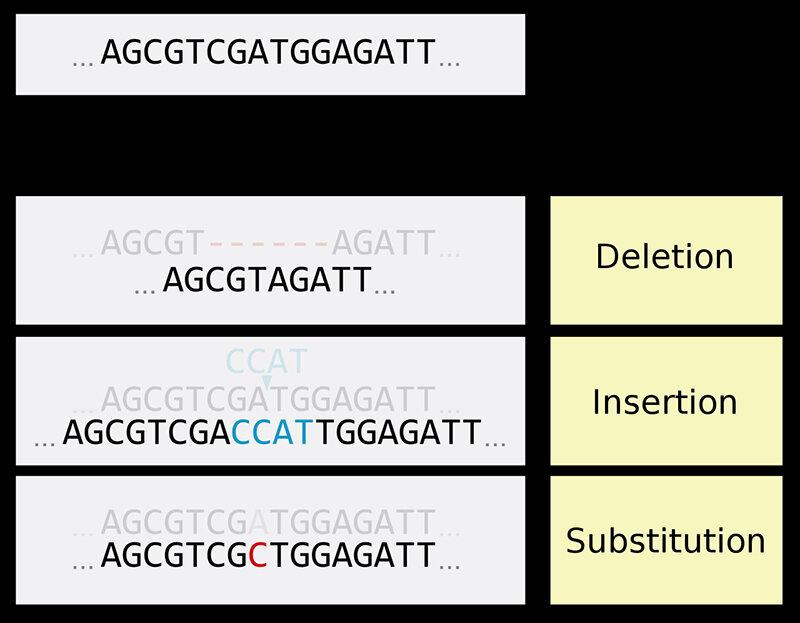

For over 30 years since the double helix structure of DNA was first discovered by James Watson, Francis Crick and Rosalind Franklin (the first two being men, side-lined the third in their Nobel bid), we did not know how to edit genes. But beginning in the 1990s, humans began figuring out how to insert, delete, modify or replace the genome of a living organism. This became known as gene editing, genome editing or genome engineering. When it is done on foetuses or babies, the popular cultural term for it became – designer babies.

Until about a decade and a half ago, we could only randomly insert genetic material into a host’s genome. But since the discovery of CRISPR – genome editing targeting specific locations has become possible. So far CRISPR-Cas9 is the most accurate way of doing it, winning its discoverers – Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier (no men stealing credit thankfully), the 2020 Chemistry Nobel. Today targeting a specific disease-causing gene in an individual has become possible.

How does gene editing work

Haemophilia is an inherited genetic condition where a mutation in a gene called F9 shuts down the blood clotting protein Factor IX, causing the clotting protein to be absent or not work properly. This leads to spontaneous bleeding.

This is an incurable condition, whose patients lead heavily restricted and medicated lives to barely survive. However, at the end of November this year, a gene therapy called Hemgenix that treats patients with severe haemophilia B by delivering a replacement for the F9 gene to the liver for it to begin making Factor IX – won approval from the US FDA – Food and Drug Administration.

This treatment from the pharma company CSL Behring costs $3.5 million for a one-time dose, making it the most expensive medicine in the world. In a trial that began in 2018, patients with this condition received treatment to override the DNA mutation causing it. Instead of relieving symptoms, this therapy addresses the root cause of the disease, effectively curing it.

Hemgenix delivery is simple: via an IV infusion in the arm. Other genetic cures being worked upon are even simpler to deliver: pop a pill and be cured of your condition.

Why is it so dangerous to edit genes

This sounds like magic. And for all effects and purposes, it is. Why is it so dangerous?

For starters, even the scientists who made Hemgenix do not know if it will work for a decade or through the life of a patient. This is too big a blind spot to leave to chance, especially considering that we do not yet know entirely if the editing works only on the part that is targeted, or if there are other unintended off-target side effects. Sci-fi horror films show this as humans growing an extra limb, an exoskeleton, sharper teeth, claw-like nails etc. Though that could happen in theory, the actual side-effect could be subtler and at times worse e.g., it could increase the propensity for diseases like cancer, or cause unintended mutations leading to some other genetic diseases later.

(Image Credit: Wikipedia)

And the biggest problem is we do not know where or what can change and when it might manifest. Thus, a small unintended change made by a genetic cure for one disease, may not manifest in the host patient but could be passed to the offspring of that person and manifest in another generation.

And let’s not forget that if editing a gene is as simple as popping a pill, what is to stop a rogue party or nation from weaponizing it? The poison Novichok could become passe if Russian spies can simply kill someone by giving a pill that edits a person’s genes and thus kills them slowly and painfully leaving no trace in its wake.

Sullied human genome

(Image Credit: Wikipedia)

From the point of view of scientific study, the biggest danger is that the human genome which has remained unaltered for hundreds of millions of years except for the occasional, natural mutation, would be soiled forever. If gene editing, like in the 1997 film Gattaca, becomes all too common, in another generation we will not know which humans carry a pure human genome, and which an altered DNA with the seeds for something potentially harmful. This could hamper the study of life on earth and ironically could prevent newer, better cures.

Scientific research on human beings will be severely altered and hampered in the future to an extent that, like scavenging for pre-1945 shipwrecks to find iron for Grieger counters, scientists could be left scavenging ancient graveyards to find DNA unsullied by human genetic editing.

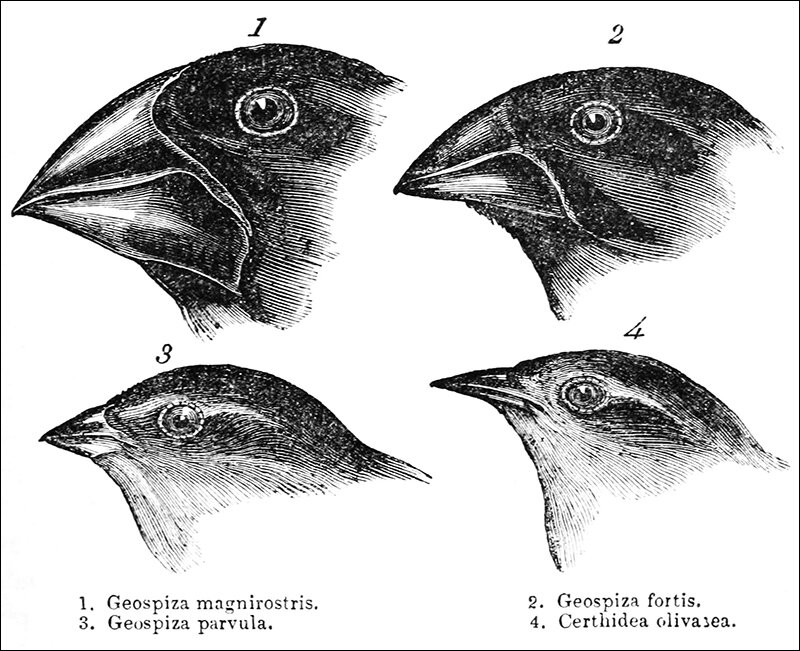

Think of a great piece of music. Every note and beat is in place for a reason. Can it be improved? Sure. Do we want to? Not really. The human genome – or for that matter the genome of any living organism – is not unlike that piece of classical music: it has been written and corrected for 2 billion years since the very first DNA appeared on the planet. Every living thing on Earth has evolved from that first DNA, branching out to form things as diverse as trees, single-celled organisms, and dinosaurs 65 million years ago to humans now. The only ones that have crafted this DNA are time and natural selection. Things that were important were kept, and useless mutations were discarded over millions of years. But for the first time in the history of the planet, we are in danger of discarding or introducing things into the human genome in the blink of an eye.

Genetic editing of plants has already been on for a couple of decades. Genetically modified crops like that of corn, potato or BT Cotton are a reality today. The idea of eliminating Malaria by introducing genetically modified mosquitoes is already being tested, much to the chagrin of ethicists and biodiversity experts.

The only remaining, pure genome has been that of humans. But with genetic modification becoming easier and more widespread, this is set to change drastically in the coming decades. What will be its consequences: we will only know when it is too late.

The past is never dead. Good, bad or ugly, it guides us into the future. The contamination of the human genome, of the genome of every species on the planet, is like erasing this past. By contaminating this, we threaten our own future before we fully understand it. It may be inevitable, but hopefully, humanity will at least go towards it with our eyes open.

In case you missed:

- A Howl Heard Worldwide: Scientific Debate Roars Over an Extinct Wolf’s Return

- Reversing Heart Disease: Next Step in Living 150 Years Achieved in Lab

- How Old Are We: Shocking New Finding Upends History of Our Species

- Prizes for Research Using AI: Blasphemy or Nobel Academy’s Genius

- When AI Meets Metal: How the Marriage of AI & Robotics Will Change the World

- Copy Of A Copy: Content Generated By AI, Threat To AI Itself

- Are Hallucinations Good For AI? Maybe Not, But They’re Great For Humans

- How Lionsgate-Runway Deal Will Transform Both Cinema & AI

- Rethinking AI Research: Shifting Focus Towards Human-Level Intelligence

- AI’s Top-Secret Mission: Solving Humanity’s Biggest Problems While We Argue About Apocalypse

2 Comments

Well, the author should probably read a bit about genetic engineering before writing such confusing stuff. There is a difference between germ line and somatic editing. You cant change your germ line by “dropping a pill”. There are easier and more “natural” ways to kill a person than to use editing: take . Just take some all natural, organic ricin, botulinum toxin or alpha-amanitin. It will do the job much more reliable than editing.

“The human genome remained unaltered for hundreds of millions of years.” Well, homo sapiens is about 300.000 years old. I do not assume that the author has the “unchanged genome” of Lucy, the Australopithecus who lived about 3.2 million years ago.

The article is littered with wrong “facts”, wrong assumptions, wrong conclusions.

One has to be careful with genome editing, especially when it comes to the germ line. But essentially none of the reasons given here is valid – there are quite other problems.

Do not even read this article when you have no basic education in molecular biology and genetics – you’ll get very confused and learn wrong things!

Thank you for your response Wolfgang Nellan.

Let me first start by telling you where you are right and thanking you for pointing it out. “The human genome remained unaltered for hundreds of millions of years.” that is a patently wrong statement. You are right about that. What I should have written, and what I meant was this: “The genome of life on earth remained unaltered for hundreds of millions of years by anything other than necessity i.e. natural selection and this natural mutation, would be soiled forever by rapid changes being made by humans thanks to CRISPR.” I will try to make the change in the article.

You are right about there being a difference between germ line and somatic editing. The problem is, there is a debate about if somatic gene editing does not pass to future generations. It is still an area of active research and there may be some exceptions or unknown factors that could lead to changes being passed down to future generations. Additionally, it’s important to note that even if the changes are not passed down, it’s still possible that somatic gene editing may lead to unintended consequences or side effects which could affect future generations, and therefore, long term safety studies are needed before bringing somatic gene editing into clinical practice.

Please do read about this emerging field where things are still not certain and we are just figuring it out.

I see that one of your main problem is the bit about being able to pop a pill and have your genes altered. You are right that it is currently difficult to do so. However, there are many companies that are developing just such a cure where a pill can be taken and it can edit a gene. You can search old uncle google about it and you’ll find that such cures are not yet effective, but it’s just a matter of time before they will be. You’d be right to call it speculative. But please remember that changing your gene by just an injection was also speculation 20 years ago but people were working on it. Things change because, gratefully, scientists have imagination and they demand that writers like me – ill-informed as we may be – have an imagination as well.

So once again, thank you for your warning. You are right. Yet you do need to grow an imagination about the potential of this therapy as well. All the best.