True brilliance is always found in the most unsuspecting places, like who would think a slime mould could design a railroad?

The world of microbiology is like an entire other planet that exists alongside us but is just too small to see. If you’ve watched the Netflix documentary Fantastic Fungi or the hit post-apocalyptic show The Last of Us, you know exactly how beneficial or deadly this world can be.

We don’t often think about microorganisms when we talk about intelligent creatures, in fact, most of us don’t think about microorganisms at all. What’s interesting about this story though, is that a single-celled organism that technically does not even have a brain proved that its intelligence was on par with an entire team of Japanese engineers.

Often mistaken for a fungus, Slime Moulds are a wide group of soil-dwelling, brainless amoeba that typically contain multiple nuclei.

Slime Networking 101

Raphael Kay, a graduate researcher at Harvard University studies slime moulds and sea creatures in order to design cities and buildings more efficiently. In an interview with Phys.org, he was quoted stating, “Humans aren’t the only ones dealing with the challenge of designing efficient, resilient networks.”

When a slime mould encounters food, it doesn’t pick it up and eat it like us but rather surrounds it with cells and then creates an efficient network of tunnels to distribute the acquired nutrients. When it encounters multiple food sources, however, is when the magic starts and It’s this ability to efficiently select the best possible routes that have scientists perplexed. So much so that a team of Japanese scientists decided to put this theory to an actual test.

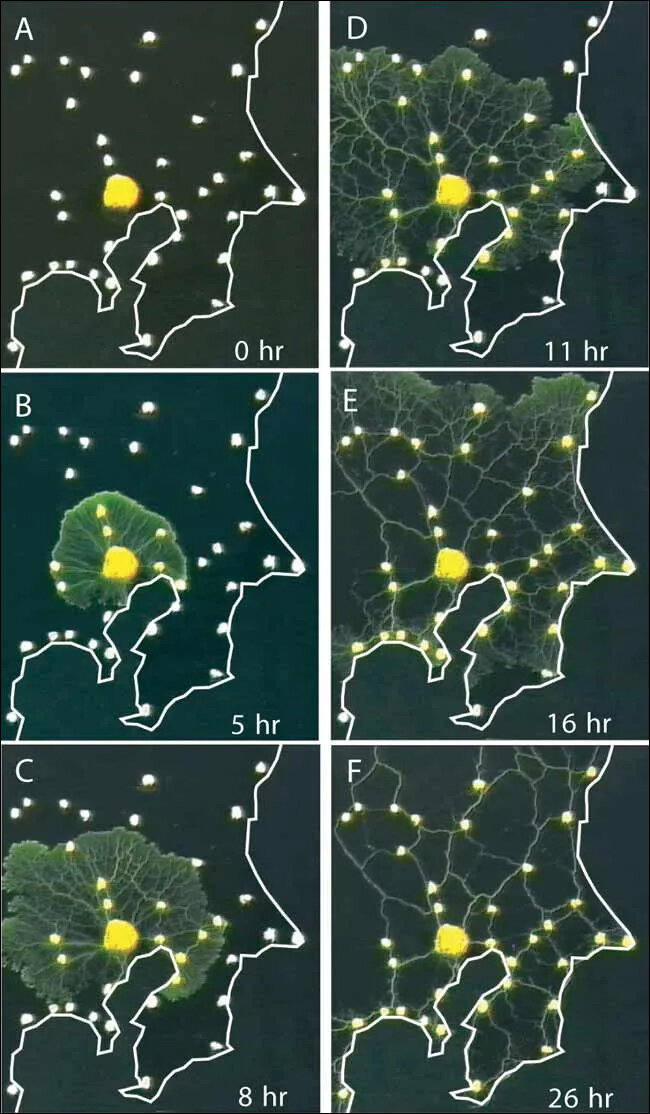

Using a map of Tokyo with oat flakes placed at each railway station in order to represent the different destinations on the railway route, researchers at Hokkaido University in Sapporo, Japan let a yellow slime mould loose on their “virtual” city. As slime isn’t particularly fond of light, they increased the lighting around areas that represented obstacles like lakes or mountains for the slime mould to avoid.

The slime mould, known as Physarum polycephalum, is said to have created an intricate network of tunnels to connect to each oat flake destination, in a way that was almost identical to the existing Tokyo railway system. In fact, in some ways, the slime mould’s design was found to be even more efficient and resilient than the actual railway route.

Biologically inspired network designs

Now the way the slime works is by spreading out over everything initially, and then cutting back the unwanted material till only the network remains. This can be compared to covering a whole city with roads or railways and then by the process of elimination, removing the unwanted ones. While we can’t practise or reproduce this process in real life, we can virtually.

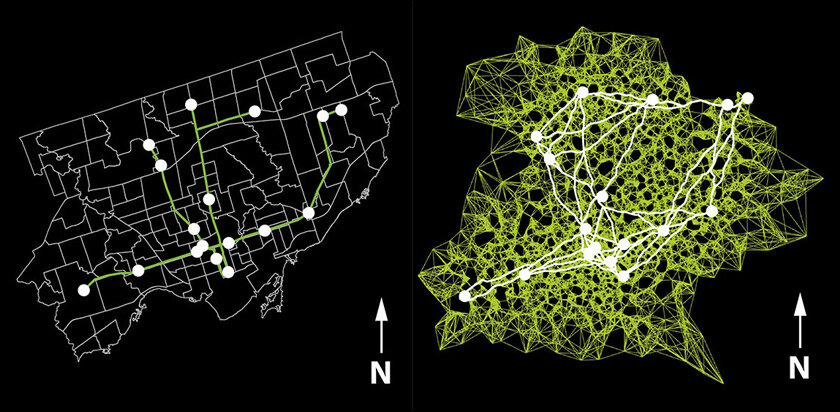

Raphael Kay, who we mentioned earlier, along with Anthony Mattacchione, an architecture student, replicated the slime’s mechanism in the form of a mathematical description that can be programmed into a computer. The software works in a similar fashion to the slime mould by laying a mesh over an entire area and then gradually cutting back while strengthening important routes and diminishing unimportant ones.

His team then conducted further tests on this slime mould computer model by getting it to network roads around a theme park in Canada, and rails around a subway system in Toronto. Kay was quoted in an interview with Phys.org stating, “For the subway, the most striking finding was that for a network with the same travel time as the real thing, our network was 40 percent less susceptible to disruption.”

Additionally, he also claims that for the Canadian theme park scenario, his slime network was not only 10% faster, but also 80% more resilient to disruption than the current one, and at the same cost. An interesting side note is that both Kay and Mattacchine originally intended the slime computer model to be used in a graduate architecture course.

Slime craft

Now in case you’re wondering how a slime mould can accomplish these feats of engineering without a brain, the answer is hundreds of millions, and possibly even billions of years of practice. While human beings have been building roads for a few thousand, and railways for a few hundred years, slime moulds have been optimising their approach to “networking,” or eating as we would call it, for over 380 million years, with some species being rumoured to exist as far back as 2.1 billion years ago.

Just goes to show, you don’t even need a brain to be intelligent, and true brilliance is always found in the most unsuspecting places, like who would think a slime mould could design a railroad?

In case you missed:

- This computer uses human brain cells and runs on Dopamine!

- Lab-Grown Brain Thinks It’s a Butterfly: Proof We’re in a Simulation?

- Mainstream AI workloads too resource-hungry? Try Hala Point, Intel’s largest Neuromorphic computer

- Scientists gave a mushroom robotic legs and the results may frighten you

- Researchers develop solar cells to charge phones through their screens

- Prophetic Halo: Turning Dreams into Conscious Playgrounds

- Could Contact Lenses be the Key to Fully Wearable BCIs?

- NVIDIA’s Isaac GR00T N1: From Lab Prototype to Real-World Robot Brain

- Quantum Computers: It’s now 20X easier to crack Bitcoin encryption than we thought!

- Pi Coin vs Bitcoin: Round 2, Mainnet Launch