A female PhD scholar is battered with patriarchy, insensitivity, juvenile dress codes and what can only be described as a form of slavery, all of which hampers India’s rise as a scientific superpower, writes Satyen K. Bordoloi.

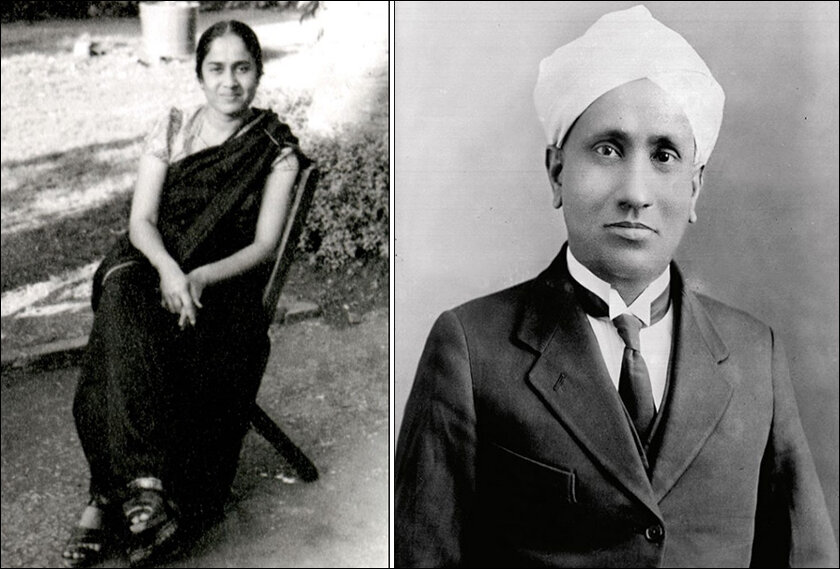

By every account, Kamala Bhagvat (Sohonie after marriage) was a brilliant woman. She had a BSc degree in chemistry, which in 1933 was a huge deal. She applied to the Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, for a research fellowship but was turned down by the then-director and Nobel Laureate Prof. C V Raman on the ground that women were not competent to pursue research. Raman was an upper-class, upper-caste, privileged man born into the prejudices of his times. Yet, how this is a stain on him can be judged by how two decades ago, Albert Einstein had stood up for Marie Curie when slander was thrown at her for having an affair.

90 years later, you’d think things would have changed for women. When ISRO launches any mission, the media lauds the saree-clad women whose science made it a success. There’s just one problem too many problems with that. If we had achieved true equality, we’d not need to reference gender while praising achievements. Secondly, if you look at the percentage of women in ISRO or any other scientific establishment, it’s abysmally low. Tabling data in Rajya Sabha this March, the government said that India has 56,747 female researchers out of a total of 3.42 lakh in various R&D establishments making a total of 16.6 per cent.

Thirdly, videos from ISRO and other establishments generally show women, instead of being intermixed with men – siloed in their own groups as if you’ll miss them if you don’t put them together. Perhaps, they’re allowed only a particular kind of work, hence are found together under that permitted department.

The regressive Raman Effect against women 90 years after the scientist’s infamous run-in with a brilliant woman, seems all-pervasive. The reasons – as I discovered talking to PhD scholars over the years – are many. It may not be as bad as it was for Kamala in 1933, but it isn’t as equal as female scientists and researchers are treated in Western nations either. That’s a shame because even these Western nations do not yet treat women with the ideal equality.

We must hence talk about what ails women doing science in India. Especially because 2023 has unwittingly become the year of acknowledgement of women in science since of the five categories of the Nobel prize, women have been awarded in three. If we can worry about India’s Olympics medals tally, why not our science prize tally. The path to a golden future for our nation can only be paved with the shovel of acknowledgement of present problems. Here, we begin by outlining how the PhD institutions and guides discriminate – not always directly – against their female scholars.

ABCD PhD:

In India, many families prefer to send girls to gender-segregated schools and universities. India has hence one of the highest numbers of women-only schools and colleges. There are different ways to look at this phenomenon. A positive one would be to see such places as a safe haven for women to study without the encumbrance and oversight of men around. From what I have heard over the years, this does happen in a good number of all-women’s institutions. If a girl goes to her teacher informing them of period-cramps or backaches, a female educator in an all-woman’s college has a better chance of understanding it. Yet, the full picture is far from rosy.

Firstly, the social expectations of women are at odds with what most women want from themselves. A man in India is encouraged to follow his passions and do good in his chosen line. For a woman, this reverses. It doesn’t matter how successful or brilliant she is; she has to be good in the house. Ex-Pepsi CEO Indra Nooyi created a furore in 2014 when she talked about the day she was anointed the president of the company and went home to tell her mother who instead asked her to go get milk even when Nooyi’s husband had been home hours earlier. When Nooyi complained telling her the good news, her mother said: “You might be president of PepsiCo… But when you enter this house, you’re the wife, you’re the daughter, you’re the daughter-in-law, you’re the mother. You’re all of that. Nobody else can take that place. So leave that damned crown in the garage.”

That is the problem: a woman’s worth is mostly judged based on what she can do inside the house for others, and how she can cook and take care of children and family.

Female PhD scholars are subjected to the same expectations. Their PhDs are seen as a means to a second income for her husband and in-laws if she’s married. If she’s unmarried, a PhD is meant to make her stock goes up in the marriage market: after all who wouldn’t like a second income? No one thinks of the contribution they could make to national and global science. Married scholars are pressured to bear children like every other woman and repeatedly told they are incomplete without one. And if a scholar has one during her PhD, her science is seen as an impediment to her motherhood and accusations – direct or tacit – are hurled at her for putting science before the child.

In India, a woman is judged not on her own inherent worth, but by the expectations society loads on her and how she fulfils or fails at it.

(Image Credit: Twitter)

CLOTHES, CASTE, PERIODS:

A PhD scholar was not assigned the professor most ideal to guide her research despite protests. It took her a year to figure out why. Scholars in her institution are mostly paired with guides based on their castes. An upper-caste scholar would be given an upper-caste guide and so on. Some did get the professors best suited to them. But only an upper caste scholar had the choice to work under lower caste guides. This was done, ironically, for the sake of science. Since both guide and scholar had to work closely together for years, the logic went that conditions should be made such that caste does not get in the way of science.

A South Indian PhD scholar told me her guide – a Tam Bram – is so particular that she has seen her in shops not take money directly from the hand of shopkeepers as she didn’t want ‘caste pollution’. This guide, a PhD herself – also believes in karma e.g. one of her beliefs is that you are born a woman in this life because of sins committed in a past life.

Another scholar couldn’t enter the cabin of her female professor guide for a week every month during periods. This delayed letters, applications, approvals, time-bound reports etc. that she needed her guide to sign and approve. Once, desperate to get her paperwork done, she entered the cabin anyway. The professor reprimanded her to which the woman told the god-fearing guide that even her periods were created by the same God. The scholar had to suffer the consequences of her comments for months.

At another all-women’s institute, how the scholars dress takes priority. Instead of being a place of liberation, freedoms are curbed in the name of ‘tradition’ with rules that are never imposed on male colleagues and staff. At special functions and on a particular day of the week, women are expected to wear sarees without exceptions. Even those who do not have saree in their culture like scholars from the tribal regions of the NorthEast, are forced to comply. One scholar who resisted found out that the implicit punishment was severe. Her paperwork wasn’t signed on time. She was refused critical meetings by her guide and other professors looked down upon her. Ironically, the scholar who told me this met a senior who had done her PhD from the same institute over a decade ago and said there were no rules like this then.

In another institute, every student is forced to wear clothes that cover their ankles. If even a portion of the ankles is visible, they are reprimanded and told to go change and come. Weirdly, this is at an all-woman’s institute and these rules are forced even on PhD scholars.

Won’t a female scholar who lives under enforced rules like dress codes, find it humiliating that an adult male student is looked at as a person who can make his own choice but a woman is denied the autonomy even in clothing?

SLAVE LABOUR:

In most institutions across the nation, the scholars – both men and women – have to be slaves to their guides. Scholars across the world are expected to help their guides as teaching assistants because it prepares them to be professors. However, in India, most guides use their PhD scholar as their personal assistants or servants. Taking lectures and practicals for undergraduates and post graduates in their place is fine. But asking them to babysit for them, and do their housework and groceries among a host of other non-scientific things, saps the energy of these scholars. Often, guides take up additional administrative work solely because they rely on their scholars to do it all while they take the credit and financial benefits from it if any.

Most of the scholars I talked to said that being a PhD scholar was like doing a full-time job with the PhD becoming the moonlighting hustle. After a day spent doing endless work for their professors, few have time or energy left to do their own research. This often results in them conducting the simplest of research projects just to meet their academic targets instead of exploring creative projects and developing new ideas in their fields.

And God forbid if the PhD scholar is also a mother. Lucky her if she has a supportive husband and in-laws. But generally, science and motherhood are forced to clash. Institutions – at least all-women’s ones that would naturally have a larger number of women with children – could provide creches and caretakers to take care of scholar’s children, but few do. Scholars with children have to take leaves to take care of their children’s illnesses, issues of their parents-in-law, parents-teachers meetings of their kids etc. How many male PhD scholars have to deal with those?

Many of these issues are common to both male and female scholars. However, the collective weight of all these issues with the extra problems thrown at them for being women, puts extra stress on their minds and bodies. The odds are stacked so high against women scholars in this nation, that those who complete PhDs, are living miracles.

THE RAMAN- EFFECT:

The Raman Effect – scientifically speaking – is the change that occurs in the wavelength of light when a light beam is deflected by molecules. In Indian science, the Raman Effect is the discrimination that women like Kamala Sohonie have had to face in the pursuit of science. But, there’s a happy ending to Kamala’s story.

Kamala was a woman made of a diamond will. She refused to give up science – as I imagine many other women must have done at the onslaught of the ‘wisdom’ of Sir Raman. Instead, she adopted the most popular protest method of the time, Satyagraha, to put her point across. Embarrassed, C V Raman relented but on four conditions: she would not be admitted as a regular student, would be on probation for the first year, her work wouldn’t be officially recognised until Raman himself was satisfied with its quality, and she would do nothing to spoil the environment by being a ‘distraction’ to her male colleagues.

Kamala gulped this humiliation and accepted the conditions. By doing so, she inspired an entire generation as the same institute saw a number of women applying the next year and a chastened Sir C V Raman did not put special conditions to their admissions except those also applicable to men.

Kamala did kamal – wonder, and became the first female PhD scholar in a scientific discipline in India. But I wonder, what if C V Raman, like Einstein, had the ‘superpower’ to see brilliant women’s science rather than look at them through the discrimination of his privileged gender, take her as a protegee and guide her like he did men? Could she have become India’s first Nobel laureate in science? Likely so. And this will be our litmus test: the day an Indian woman wins a Nobel prize in a scientific field, we can call it the beginning of the end of the nightmare of trying to be female scientists, in a man’s world.

DISCLAIMER: Names of people and places have deliberately been changed, omitted, left out or obscured to prevent detection of those who’ve spoken on conditions of anonymity.

In case you missed:

- Prizes for Research Using AI: Blasphemy or Nobel Academy’s Genius

- Tears of War: Science says women’s crying disarm aggressive men

- Are Hallucinations Good For AI? Maybe Not, But They’re Great For Humans

- Quantum Leaps in Science: AI as the Assembly Line of Discovery

- Reversing Heart Disease: Next Step in Living 150 Years Achieved in Lab

- How Old Are We: Shocking New Finding Upends History of Our Species

- India’s Upcoming Storm of AI Nudes & Inspiring Story Of A Teen Warrior

- Susan Wojcicki: The Screaming Legacy of The Quiet Architect of the Digital Age

- When Geniuses Mess Up: AI & Mistakes of Newton, Einstein, Wozniak, Hinton

- Why Elon Musk is Jealous of India’s UPI (And Why It’s Terrifyingly Fragile)

3 Comments

Hey, it’s a nice blog till now I have seen on the internet. It’s a good blog according to the information you have provided in it.

A powerful reminder of the deep-rooted challenges women face in science even today. 🚫⚖️ Despite progress, the path to true equality remains steep. We must continue to shine a light on these issues and strive for a future where brilliance, not gender, defines success. 🌟👩🔬

The struggles of female PhD scholars in India highlight ongoing issues of patriarchy and gender inequality in science. Despite progress since Kamala Sohonie’s time, women remain underrepresented in research, facing systemic discrimination and restrictive environments. Recognizing and addressing these challenges is crucial for India’s aspirations as a scientific superpower. Acknowledging female achievements in science is essential for paving a more equitable future. 🌟👩🔬 #WomenInScience