SpaceX and xAI want to lift entire data centres off Earth and into orbit, doing it easier fantasised than done, writes Satyen K. Bordoloi

Those born before the Internet era think that “data in the cloud” literally means your data rests somewhere in the sky. So far, it was a joke. But if Elon Musk and a few others have it their way, your data would actually live even beyond the clouds, up in the sky.

By merging his rocket company, SpaceX, and his AI venture, xAI, Elon Musk wants to enter sci-fi territory: he wants to build a constellation of a million satellites to serve as data centres in space, powered by the sun, thus bypassing the energy crisis and environmental constraints we see on Earth.

WHY RELOCATE TO SPACE

Generative AI models guzzle staggering amounts of electricity, both for training and operation, pushing data centres to their limits and straining power grid and water resources required for cooling. Musk wants to leverage the unique environment of low Earth orbit (LEO) by putting “orbital data centres” to tap into continuous, unfiltered solar power.

He wants to build a vast network of satellites, each acting as a self-contained, solar-powered server farm, with energy-intensive AI training and computation in orbit, powered by sunlight and cooled by the low temperature of space.

HOSTILE ENVIRONMENT FOR SERVERS

Experts point out that space is brutal for computing hardware for four major reasons. On Earth, data centre heat is dissipated via air and water cooling. But space is a vacuum that traps heat, which means revolutionary cooling systems would be required for the process.

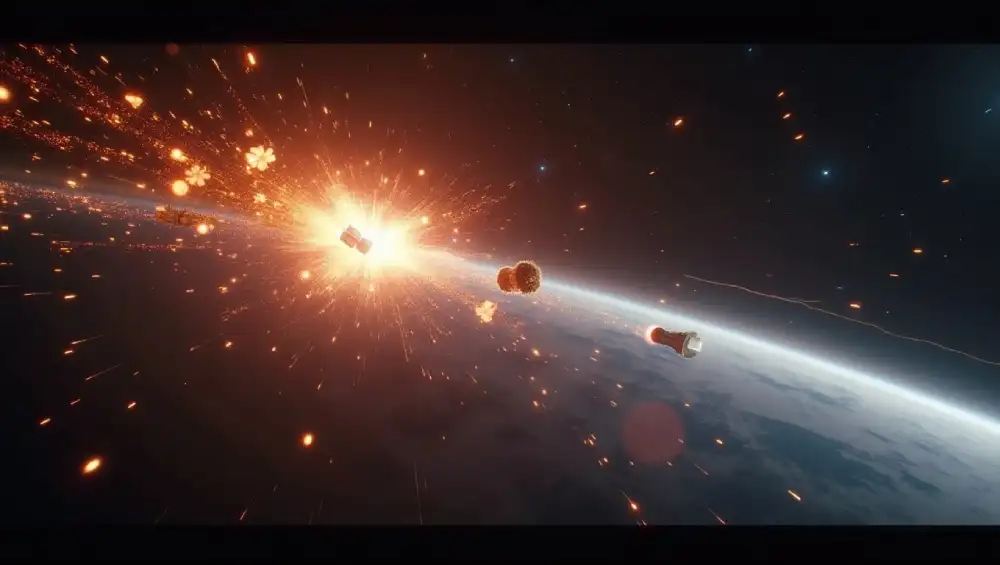

In the film Gravity, space debris triggers a cascading series of catastrophes that the protagonists must struggle to survive. Space already has over 15,000 active satellites. Adding another million would dramatically escalate the risk of collisions and, with objects travelling at 17,500 mph, would create a cascading debris field, a phenomenon known as Kessler Syndrome, making LEO unusable.

On Earth, if a GPU fails, you’ll have a technician swap it. But how do you do so in orbit? On top of that, hardware is bombarded with high-energy radiation, which can degrade components. Solutions could be found, but it would add to the cost and complexity.

And beyond supply chain compromises and harm from debris, they are prone to the same threat of hacking and remote access, making the task of securing them – both its hardware and software – monumentally challenging.

Atop it all is Musk’s declaration of a 30-36 month timeline is extraordinarily aggressive, particularly when xAI is burning through cash very fast, approximately $9.5 billion in the first nine months of 2025. However, merging with SpaceX, which is preparing for a massive IPO, could provide a cash infusion, not to mention the favourable political climate.

MUSK’S COMPETITION IN SPACE

That is perhaps the reason Musk isn’t the only one in the fray. There’s Starcloud, backed by NVIDIA, which is developing space-based AI training data centres and is planning a demonstration this year. Axiom Space is also developing an orbital data centre module as part of its commercial space station and plans to launch its first module this year.

Lonestar Data Holdings, meanwhile, is focused solely on data storage, not computing, and tested a small data centre on the Moon in 2025, with plans to launch a dedicated data storage satellite by next year. Thales Alenia Space (ASCEND Project) is a European Commission-funded feasibility study for eco-friendly, sovereign space-based data centres, aiming for a first in-orbit demonstration mission by 2028.

OrbitsEdge plans to develop compact, high-performance micro data centres for deployment on satellites.

And let’s not forget the Chinese, who are fielding experimental “space data centre” constellations. One Beijing programme plans space data centres in near-continuous sunlight at 700–800 km altitude, targeting many gigawatts of solar power across several phases over the next decade. Other Chinese efforts, such as the Xingshidai constellation, aim to harness solar energy and in-orbit processing for AI-heavy applications from defence analytics to autonomous systems.

FEASIBILITY AND THE MUSK PARADOX

The key question driving all this remains the same: Is it feasible? Market analysts project growth for in-orbit data centres, but note that, from a very small base, it may reach about $39 billion by 2035. Sceptics argue its economic case is weak, considering that the cost of launching heavy, radiation-hardened hardware remains astronomically high despite falling launch prices, not to mention the high operational risk.

Yet we all know that, love him or hate him, we can’t deny that he’s a maverick. And assessing his plans through a conventional feasibility matrix may miss the point entirely. That’s because his strategy is familiar: declare an audacious goal to shift the Overton window of possibility, leverage vertical integration across his companies to control costs, and use the publicity to attract capital and talent.

The merger and IPO plan very deliberately harnesses the investor frenzy around AI to fund a long-term space infrastructure vision. It is a power play by Musk that dares the market and regulators to keep up.

And when problems occur, which they inevitably will, either from a failing satellite, debris creation from collision, or even failed hardware, the response will test the resilience of the entire model. It will depend on the yet-to-be-perfected technologies for autonomous management, debris mitigation, and perhaps in-orbit servicing via robotics.

This would turn every anomaly into a high-stakes crisis, and perhaps even an opportunity, as new technologies that do not exist will have to be invented for the same, pushing the race forward.

What Musk is proposing isn’t just orbital data centres. He is asking us to shift our ambition to the sky. If building rockets was the first step to becoming a space-faring civilisation, data centres in space are the next. And the technology we invent for this will push us further into that spacefaring dream. And that is Musk’s ambition, because he filed with the FCC that the million solar-powered satellites in LEO aim to see “humanity becoming a Kardashev II-level civilisation – one that can harness the Sun’s full power.”

He is framing the project in terms of humanity’s long-term survival and advancement, and is attempting to solve AI’s imminent Earth-bound energy crisis by merging it with his vision for a multi-planetary species.

Whether this finally results in a functioning orbital cloud or remains a provocative but impractical dream will depend on overcoming physics and economics at a scale humans have never attempted.

Yet one thing is certain: the race to build infrastructure in space has not only begun but has also been given a booster rocket. And whether Musk succeeds or not, the fact that the Cloud will move literally beyond Earth’s clouds is certain.

In case you missed:

- Why is OpenAI Getting into Chip Production? The Inside Scoop

- Free Speech or Free-for-All? How Grok Taught Elon Musk That Absolute Power Corrupts Absolutely

- The AI Prophecies: How Page, Musk, Bezos, Pichai, Huang Predicted 2025 – But Didn’t See It Like AI Is Today

- NVIDIA’s Strategic Pivot to Drive our Autonomous Future with Innovative Chips

- Forget Chernobyl: Your Instagram Feed Might Cause The Next Nuclear Disaster

- Quantum Internet Is Closer Than You Think, & It’s Using the Same Cables as Netflix

- The Digital Yes-Man: When AI Enabler Becomes Your Enemy

- Alchemists’ Treasure: How to Make Gold in a Particle Accelerator (and Why You Can’t Sell It, Yet)

- The Growing Push for Transparency in AI Energy Consumption

- AI’s Looming Catastrophe: Why Even Its Creators Can’t Control What They’re Building