Tech’s founding prophets called the AI Revolution decades early, and got quite a few things wrong about it, finds Satyen K. Bordoloi

In the distant past, the future was easy to predict. This millennium, the future has not remained the same as it used to. The exponential growth in technological advancements has made the prediction business kaput. Not entirely, though. Recently, an interview Larry Page gave in 2000, in which he discussed a system that would “understand everything on the web” and deliver precisely what a user wanted, resurfaced and has sparked people’s interest.

Page was not the only one. Silicon Valley’s most influential founders have dabbled in fortune-telling, conjuring visions of an AI future ranging from the practical to the apocalyptic. Most of them were directionally correct, yet the gap between that and today’s messy reality fluctuates between hilarious and occasionally dangerous. Here, I take you back to the past to see which of our tech luminaries talked about AI, who got it right, and who didn’t.

LARRY PAGE

Larry Page wasn’t pitching sci-fi with his understand-everything search engine. It was a vision of AI that has today come true with eerie precision in Gemini, and “AI Mode” in Google search, which turns web content into conversational answers rather than just listing links, all backed by infrastructure that would have seemed sci-fi in 2000. The strange irony is that Page got the direction absolutely correct while simultaneously failing to anticipate that his “ultimate search engine” would occasionally insist that the Eiffel Tower is in Berlin or that you can walk the English Channel.

JEFF BEZOZ

Jeff Bezos grasped a truth that Page and others overlooked in the heyday of AI: most of AI’s impact would be invisible. In shareholder letters in the 2010s, Bezos described machine learning not as a flashy consumer product but as quiet infrastructure embedded in recommendation systems, fraud detection, demand forecasting, and logistics optimisation. His vision was of an organisation so suffused with algorithmic decision-making that users would never think twice about it.

Bezos was essentially predicting that AI would become like electricity: omnipresent, foundational, powering everything, yet entirely unglamorous.

Today, Amazon’s reality has confirmed his thesis. AWS offers machine learning services as basic utilities, while its retail empire runs on algorithms that learns and adapt to customer behaviour at scales that would have required armies of analysts in the pre-AI era. Despite this, Bezos never anticipated that these invisible systems might encode bias, that they might make algorithmic decisions about worker scheduling that prioritise efficiency over human dignity, or that the concentration of such power in a handful of corporations should warrant societal concern.

Maybe his vision was incomplete, not because he was wrong, but because he was looking for profit and operational efficiency, not for the social fabric it might end up shredding.

ELON MUSK

Elon Musk is an excellent case study of a ‘change of heart’ on AI. As early as 2014, he cast artificial intelligence as “potentially more dangerous than nukes,” citing superintelligent systems that might regard humanity as an obstacle. In response, he co-founded OpenAI in 2015 with Sam Altman, explicitly framing it as a nonprofit hedge against what he feared would become a Google monopoly in frontier AI research and, by extension, all AI and its governance.

Musk’s early vision indeed carried a kernel of truth about the strategic importance of AI and the dangers of concentration. Yet, his private communications told a different story entirely. A 2018 email revealed that he saw OpenAI talent and research as potential accelerants for Tesla’s full self-driving program – less a safety venture and more a competitive weapon. The irony is complete now, as on the one hand, Musk decries the existential risks of AI while simultaneously building his own AI ventures to compete head-on in the frontier-model arms race he once warned humanity against.

Today, his rhetoric and erratic behaviour, both in public and when it comes to AI, have become a danger in themselves. As for his early warnings, they weren’t entirely wrong – instead, they seem to parody him as it is clear today that in a genuine arms race, the side shouting loudest about danger is often the one most eager to arm itself faster and thus put everyone else in danger the quickest.

JENSEN HUANG

Jensen Huang, though less vocal than Page or Musk about grand AI visions, has made the most consequential – and let me add, profitable – early prediction of them all. In the 1990s and 2000s, when Nvidia was struggling, Huang identified something the tech industry had largely overlooked: the future would belong to companies that could enable parallel processing at scale. Most computers were built around central processing units designed for sequential tasks, a bottleneck for computationally intensive work.

Nvidia bet everything on graphics processing units, chips capable of handling thousands of operations simultaneously. When the company released CUDA, its parallel computing platform, in 2006, few recognised it as revolutionary.

Within a few years, though, researchers began using Nvidia GPUs to train neural networks at speeds that would have been impossible with traditional CPUs. Thus, by the time deep learning exploded in the early 2010s, Nvidia was the only company truly prepared to supply the hardware underpinning the AI revolution. In 2016, Huang personally delivered Nvidia’s first AI supercomputer to OpenAI. Today, Nvidia is so critical to the AI ecosystem that it has become the de facto infrastructure layer for every frontier model.

Huang’s early vision was not about AI itself but about the computational substrate that AI would require. He was essentially correct decades before the world understood what he was building toward – and his early bet has paid off with his company nearing a $5 trillion valuation – the first ever in the world, and more than most nations’ GDPs. The prophecy here was not about intelligence; it was about the plumbing. And his vision was worth trillions of dollars.

MARK ZUCKERBERG

Mark Zuckerberg, like Elon Musk, is a study in contrasts. He was involved with AI systems early, first with a 2002 senior project, a program called Synapse that used a form of artificial intelligence to learn users’ music preferences, and later with AI recommendation systems on Facebook and Instagram. He was one of the first to deploy AI on an industrial scale in most of his products.

Yet, somehow, Zuckerberg missed the generative AI boat entirely, betting everything in 2022 on Metaverse, including changing his company’s name. Yet, it was in the latter half of that very year, first with OpenAI’s Dall-E and then with ChatGPT, that the world tilted on its axis towards generative AI, and Zuckerberg still didn’t pivot towards it.

Metaverse flopped royally and has been losing money every year since. The tech-titan finally relented, a little at first, and they almost entirely. He has done well in this short time, first by championing open source with the release of Llama, and then by turning to a closed, monetizable model in “Avocado”, another U-turn by the company that has perhaps made the most mistakes in the AI space, yet has lived to thrive in the space.

Zuckerberg’s story, along with Musk’s, shows that AI is but a power game, and not one of talent. Throw enough money at AI, and you’ll reach world-class levels at a quick pace.

STEVE JOBS

The world of AI would have been a much more exciting world if Jobs had been alive to contribute to it. A true tech visionary (interpersonal relationships aside), he had the uncanny ability to see tech for what it can do to people and build products centred around that vision. From Lisa to the iMacs, Pixar, and then iPods and iPhones, he was the most radical tech visionary the digital world has seen so far.

Sadly, he passed away just when the AI boom was hitting its stride. But he left behind his vision for AI in a 1983 speech to a group of designers in Aspen, in which he envisioned a machine that, when carried by someone, would record all of that individual’s writings and ideas to enable others to interact with them long after they are gone. If you look at what companies like Replika or Character AI are doing, it is somewhat similar.

It was a remarkably prescient metaphor for what large language models now attempt to do: ingest human knowledge to synthesise responses that approximate anyone you like, from great thinkers to your favourite columnist. However, I also believe that his buying of voice agent Siri, was a path to AI in Apple devices, which has mostly been lost to Apple after his passing, so much so that instead of being the torchbearers of the tech which I think they would have been under Jobs, they had to partner with OpenAI to launch a cheekily named Apple Intelligence – sounding good in marketing, but not so much in use. Steve Jobs will hence remain one of the biggest ‘what ifs’ of the digital.

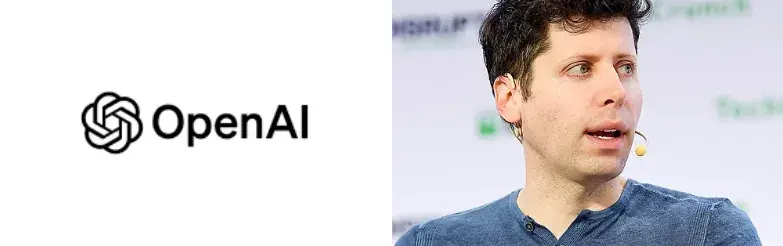

SAM ALTMAN

Sam Altman articulated a vision of artificial general intelligence as “the most important technology for the future of humanity.” Hence, by co-founding OpenAI in 2015 with Elon Musk, he sought to develop the technology with democratic principles and safety guardrails in mind, rather than a pure profit motive. However, OpenAI soon restructured itself into a “capped-profit” entity, attracting billions of dollars in investment and becoming precisely the kind of powerful, concentrated AI entity Musk had warned against, which Musk’s AI company is also becoming.

Altman’s early vision of safe, distributed AI has become a reality via his company, whose models now power a large part of the world’s conversational AI systems. He was correct about the tech’s importance, but underestimated the speed at which the market would reward whichever organisation could scale frontier models fastest.

SATYA NADELLA

Nadella, at the helm of Microsoft after Bill Gates, articulated a different kind of vision of AI, less apocalyptic than Musk, less utopian than Altman and more pragmatic than even Bezos. He saw machine learning as a tool to democratize access to capabilities that are the province of specialists. Early on, Nadella described Azure Machine Learning Service as a way to put data science tools into the hands of any organisation, not just elite researchers. His vision was pragmatic – AI as infrastructure, available to enterprises at scale.

The reality has largely borne this out, with Microsoft’s partnership with OpenAI initially, and later going solo, positioning the company to embed frontier AI capabilities into Office, Azure, and its product suite. Nadella foresaw the future accurately, but even he did not anticipate the speed at which “democratizing AI” would morph into “concentrating AI power among companies that can afford the largest compute”, his being one of them, becoming only the second 4 trillion dollar company in the world.

SUNDAR PICHAI

Sundar Pichai of, and at, Google occupies a unique place in this pantheon. Not just because – to put it cheekily – his name ends with AI, but because, despite not being the flamboyant type as other CEOs, under his leadership, Google has quietly built both the expertise and infrastructure needed to make AI, and thus the world, run. It was under him that the Transformers paper was published for the world in 2017, which led to the generative AI era we are now living in.

Pichai would later reveal that his company had held back many of the AI capabilities for years, unsure and wary of releasing them. His vision, as the de facto head of the AI world without making a fuss, has been for a less aggressive deployment and more careful stewardship. But his instinct to move carefully was overpowered by the market’s appetite for frontier models. This saw Google lag behind a bit initially, but it has caught up since, and Google is hands down the leader of the AI revolution right now, even though you do not hear grand proclamations from Captain Pichai, rather, err, umm.. Captain Pitch-AI.

As you can see for yourself, most of these founders got the broad strokes about AI right. Yet, their case has been one of missing the trees for the woods, as they got the direction right but were blind to externalities. AI would be transformative, would embed itself in infrastructure, become ubiquitous, and require massive power – they were right about all these.

What they missed was the social costs of getting there, as none fathomed the copyright chaos, the environmental impact of training massive models, labour displacement, the hazards of hallucinations, or the challenges of concentrating AI power in the hands of a few corporations. They saw the beautiful mountain peaks, not the avalanche they had packed.

The gap between early predictions and the messy, hilarious, and occasionally dangerous reality of AI in 2025 is vast. We are once again confronted with what Yogi Berra said: The future ain’t what it used to be. But the present, now that is something we have got to learn to manage.

In case you missed:

- Why is OpenAI Getting into Chip Production? The Inside Scoop

- Beyond the Hype: The Spectacular, Stumbling Evolution of Digital Eyewear

- AI’s Looming Catastrophe: Why Even Its Creators Can’t Control What They’re Building

- Free Speech or Free-for-All? How Grok Taught Elon Musk That Absolute Power Corrupts Absolutely

- Why the Alleged, Upcoming AI Crash Is Never Going To Happen

- The Growing Push for Transparency in AI Energy Consumption

- Why Elon Musk is Jealous of India’s UPI (And Why It’s Terrifyingly Fragile)

- Great quantum poker: Who’s bluffing, and who is holding the aces?

- One Year of No-camera Filmmaking: How AI Rewrote Rules of Cinema Forever

- The Great AI Correction of 2026: Why the ‘Bubble’ Popping Could be the Sound of Growing Pains