With indigenous GaN chip development, India strengthens its self-reliance in advanced radar and electronic warfare technologies.

India has quietly joined an elite club of just seven countries that can develop Gallium Nitride (GaN) semiconductor chips, a milestone defence technology once denied to it under a major fighter jet deal. The Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) announced that it has successfully developed indigenous GaN chips, the same class of compound semiconductors that underpin advanced radar and electronic warfare systems on modern fighters like the Rafale.

France, which sold India Rafales starting in 2016, reportedly refused to transfer GaN chip technology under the 50 per cent offset clause in the contract, keeping the cutting-edge tech out of India’s hands. That denial apparently became a catalyst for change, pushing DRDO scientists to pursue the hard work of mastering the chips themselves rather than depending on foreign access.

Understanding GaN Technology

GaN semiconductors are a generation beyond traditional silicon chips and use gallium combined with nitrogen instead of silicon. That’s when you get what’s being called a compound semiconductor that allows devices to operate at much higher frequencies, higher voltages, and greater efficiency, which is essential for powerful radar, communication systems, and even high-energy electronic warfare gear.

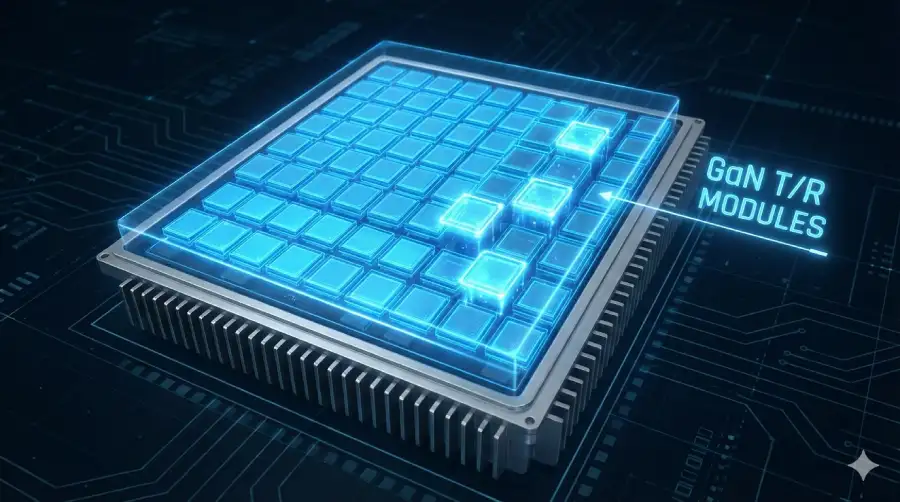

DRDO’s success focuses on making GaN monolithic microwave integrated circuits (MMICs), tiny but extremely capable chips used in systems where performance under stress is critical. Because of their performance edge over silicon, nations have been racing to develop and control their own GaN production, and India’s entry into this field signals a shift in its technological capabilities.

The GaN MMIC effort took place within DRDO laboratories in Delhi and Hyderabad. The Solid State Physics Laboratory was among the centres involved. Initial devices were produced and tested in clean-room facilities against defence performance requirements. Prototype GaN chips were built around March 2023. They were examined within DRDO laboratories as part of routine verification.

The devices were later marked suitable for further use in defence platforms. All related work took place inside domestic facilities. No external technology transfer was involved in the process. Around the same time, social media posts identified DRDO scientist Dr. Meena Mishra as one of the contributors associated with the Solid State Physics Laboratory team working on the project.

Defence Applications and Civilian Use Cases

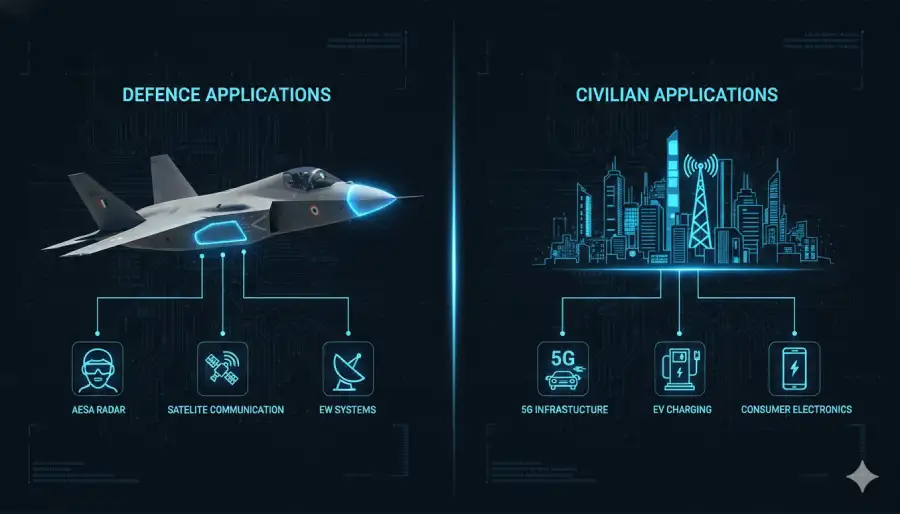

The strategic implications of this success are notable for a few reasons, the most important of which is undoubtedly radar. GaN chips are the backbone for radar and communication systems where range, resolution, power efficiency, and heat tolerance matter. India has already developed the Uttam AESA radar using earlier semiconductor platforms such as GaAs.

The availability of indigenous GaN devices provides scope for future radar upgrades with improved power handling and efficiency. GaN radar systems are typically mounted on fighter aircraft, long-range air surveillance systems, and next-generation weaponry.

These chips dramatically improve performance while reducing weight and space, critical factors in airborne applications. Indian defence scientists have referred to compound chips like GaN as the “thoroughbred racehorses” of high-performance technologies, emphasising their greater capability compared to older solutions. By producing them internally, DRDO not only cuts reliance on a foreign supply chain but also opens up future possibilities for indigenously designed radar arrays, electronic warfare suites, and secure communication networks.

GaN is not just used in military systems either, and there are a number of civilian applications. The material is already present in certain telecommunications equipment and power electronics. It is suited for applications that require higher frequency operation and improved heat tolerance. Some 5G infrastructure uses GaN-based devices, and similar components are also found in electric vehicle power systems. Because the same semiconductor platform supports both defence and civilian hardware, research conducted in one area can apply to the other.

Domestic fabrication capability means these devices do not need to be sourced entirely from abroad. The development of GaN devices within DRDO laboratories adds to India’s existing semiconductor work without limiting the technology to a single category of use.

Aatmanirbhar Bharat and the Road Ahead

India’s entry into the GaN technology club is a statement about self-reliance. Where once access to this key technology was restricted by export controls and strategic denial under defence contracts, India now boasts the ability to make these chips domestically, the Aatmanirbhar way. Within DRDO labs, the focus remains on refining and scaling production to meet defence requirements first, but the underlying capability is clear.

Critics and analysts alike see this achievement as part of a larger arc in India’s technology journey, from importer of systems to an innovator in frontier semiconductor fields.

As these chips start making their way into Indian systems and possibly future export products, observers are left wondering: if this was once a denied technology, what’s next on India’s list of strategic breakthroughs?

In case you missed:

- India’s first Aatmanirbhar Chip Fab: TATA leads the way!

- India’s first Aatmanirbhar semiconductor chip is finally here!

- Tata Electronics to Manufacture Intel Chips & AI Laptops in India!

- India’s First Paid Chip Prototype: Kaynes Fires the Starting Shot

- Slaughterbots: Robot Warriors in the Indian Armed Forces!

- Quantum War Tech: DRDO and IIT help India take the lead!

- 4 New Chip Fabs and a Rallying Cry from The Red Fort!

- One Chip to Rule Them All: The 6G Chip at 100 Gbps!

- India’s Mappls Revolution: The Swadeshi Push to Dethrone Google Maps

- India, iPhones, China & Trump: The Foxconn Story!