High costs prevent e-cycles from taking off despite India’s history as a proud cycling nation finds Satyen K. Bordoloi as he explores the solutions…

Across many old railway stations nationwide or covered by tall grass in unused corners of college, or perhaps even at office campuses, you will find metal girdles into which the front wheel of a cycle can be inserted and locked. Growing up in the 80s, I’d see hundreds of cycles neatly parked on such stands outside cinema halls or factories. Today they mostly survive in our nostalgia.

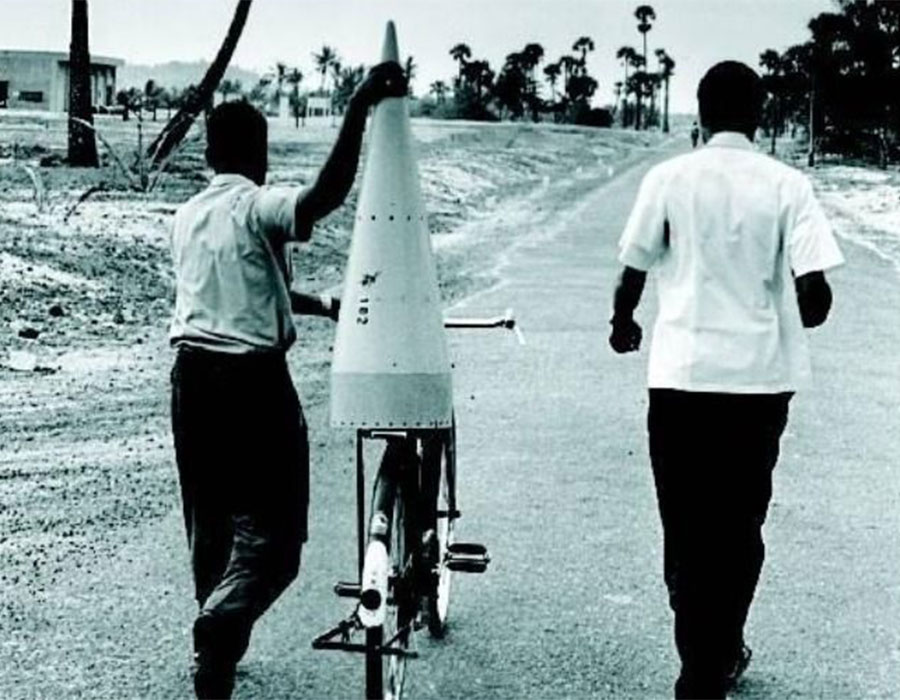

India has always been a nation of cyclists. From space rockets to a toddler’s first ride to school, to the first taste of freedom for a teenager: our go-to vehicle of choice was always this perfect metaphor for man and machine working in tandem. But in the last two decades of the new millennium, things have been the worst ever for cycles in India in its 205-year existence.

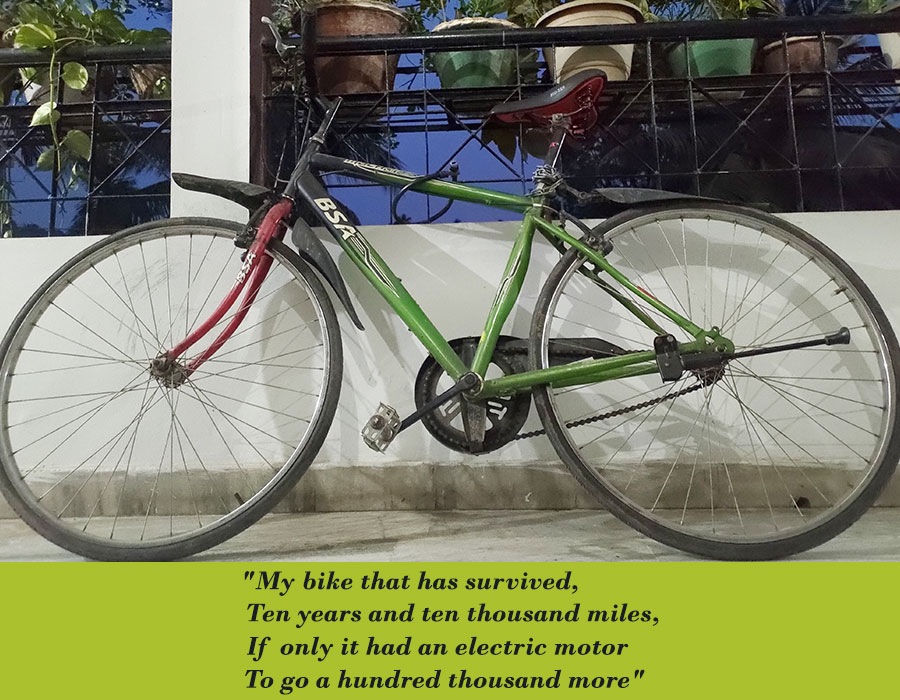

Cycles that run on electricity, e-cycles or e-bikes – with the promise of coasting at high speeds without effort, were supposed to resuscitate cycling. So far they have failed for one simple reason: high prices. Since 2011, when I abandoned my motorcycle for two cycles in two cities, I have wanted an e-cycle. Back then, there were none to buy. In the last few years many have come up but I am still waiting for prices to come down. Right now they almost cost as much as petrol two-wheelers.

An average, gearless cycle before the pandemic cost around Rs. 6000. Zap in a battery, motor, controller and some wires to connect them and voila, you have an e-cycle. That shouldn’t add much to the cost, right? But before the pandemic, the cheapest e-cycle cost around four times an average cycle. Today, it costs five times as much.

I told Apurav Jain, GM Electric Cycles at Ninety-One this, and he instantly cut me short, “That is the wrong way of looking at it. A normal cycle – tyres, tubes, frame, and other components included – is not designed for an e-cycle. E-cycles need tyres with better brakes, suspension, brake levers, pedals, cranks, thicker spokes etc. Every component has to be better.”

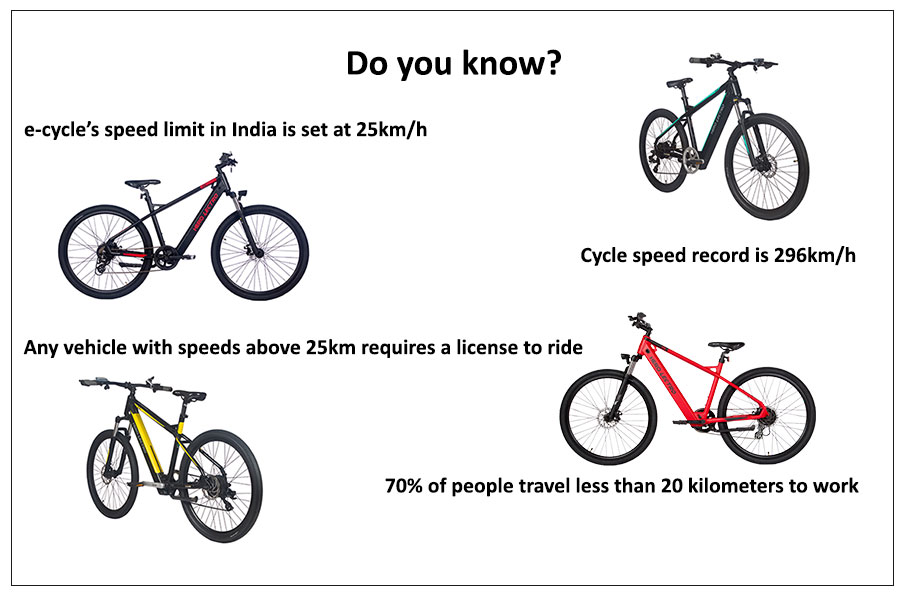

I average 15km/h for long distances. An e-cycle’s speed limit in India is set at 25km/h as higher speeds require a license (though I’ve read of rigged e-cycles that do 50km/h, small fry compared to the cycle speed record: 296km/h). For a cycle to take the strain and braking of higher speeds would naturally require better components. And let’ not forget the cost to develop and maintain electric components and a smart app.

Aditya Munjal, Director, Hero Cycles, the makers of the Lectro range – India’s cheapest and most selling e-cycles – says, “In India, 70% of people travel less than 20 kilometers to work. E-cycles are the perfect solution for this commute to beat traffic, save money and protect the environment and your health. Hence, our aim when we started Lectro 3 years ago was to provide affordable short mobility solutions to daily commuters.”

Munjal admits things haven’t gone according to plan. “Europe has seen a tremendous uptick but in India, there’s a big price gap between an average cycle and entry-level e-cycles whose price has gone up from around 22,000 a few years ago to 30,000 now.” You read that right: e-cycle prices have actually shot up thanks to the increase in the cost of metal, electronic components, lithium for batteries, supply shortages etc.

Yet, Apurav Jain reminds me, “E-cycles in India are the cheapest in the world.” He is right. But the common person on the streets does not go by logic. S/he is driven by how much heat their wallets can take. Munjal agrees and says they are working on multiple solutions. The most expensive components of an e-cycle – battery and motor – are imported. In the various R&D labs both in India and abroad, Hero Cycles is working to make them in India and make them cheap.

Both gentlemen say profits on e-cycles are wafer-thin and that normal cycles give better margins. Yet Aditya Munjal is aware a revolution is right around the corner, and he wants Hero Lectro to lead it with a unique innovation.

They are trying to convert the average, ubiquitous roadster cycle, the ones your washerman and milkman uses, into an e-cycle at an attractive price point. “We want regular people in rural or semirural districts of India to use an e-cycle. We are trying to keep the price below 20,000 but it is proving to be really difficult,” says Munjal who admits that if and when it happens, “e-cycles will take off at a much bigger level than what we have experienced with Hero Lectro.” Even bigger than in Europe, at least in numbers.

Can’t conversion kits be the solution to cheaper e-cycles? Jain explains, “The moment you put a motor, you have to make adjustments in the frame for it to fit. You will have wires hanging out and if the connections or components are poor, the cycle won’t last long. This means you will have to periodically keep changing things, increasing your cost. Besides, in changing these components, you are building a new cycle so why not go for one that is engineered from scratch?”

Again, he is right, but I refuse to give up on wanting an e-cycle cheaper. Both Jain and Munjal say the government can help in this. Both gave the example of the subsidy policy the Delhi government has announced as a good initiative if implemented.

Munjal says, “One is demand-side subsidy: where you incentivize customers to move to EVs. It will help the government meet carbon emission goals and promoting sustainable mobility as discussed in the COP26 global climate summit. The other is to provide production-linked incentives to make it viable for Indian companies to manufacture a lot of components for both cycles and e-cycles. If that happens, we guarantee cheaper prices.” Munjal says they are working with the central and various state governments to bring prices down.

He admits higher GST on some e-cycle components increase costs, but he doesn’t see it as a big challenge. Neither does Jain who instead wants incentive financing from private firms to help people buy e-cycles. What he wants from the government are cycle-friendly roads. “More people will take up cycling if they feel safer on the roads. If infrastructure gets better, people using e-cycles for commute will naturally grow,” he says. As a cyclist, I couldn’t agree more. Along with better roads, I also want better parking. I’ve had many altercations with parking attendants of shopping malls who refuse to allow me to park my cycle. That dissuades me from using it more…

“At the end of the day, people’s mentality needs to change. You have to understand that e-cycles are a better engineered and quality product than normal cycles. Secondly, you have to take up cycling for commutes. If you are using an e-cycle for leisure, how are you helping reduce carbon emissions,” questions Jain. Both of them admit e-cycles will pick up when they are used to commuting in place of motorcycles.

In case you missed:

- The swap revolution supercharging India’s mobility

- Will AI Take Your Job? Answer: Yes, No & Awesomely So

- RBI’s e₹ – will the Digital Rupee transform or trammel India

- Landscape of Fraud: India’s Cybercrime Heatmap from Jamtara to Bharatpur via Surat

- ‘Teen social media use is a dire warning for world’

- PSEUDO AI: Hilarious Ways Humans Pretend to be AI to Fool You

- Could Menstrual Blood Save the World?

- What Ails Indian Women in Science: Travails of PhD Scholars

- Bait, Hook & Catch Part 2: 15 More Common Ways Cybercriminals Cheat You

- How AI video creators like OpenAI’s Sora will change cinema forever

2 Comments

Love the research that has gone into this story.

Multiple experts have contributed to this piece making it authentic.

Satyen could have mentioned something about the future of e-cycles.

Thank you for sharing the information about Indian e-cycles and the high cost quandary, keep sharing.